Submitted by noline9 on

WATERLOO REGION — It runs straight across the region’s southern edge, under rivers and roadways, pumping a steady stream of crude oil beneath our feet.

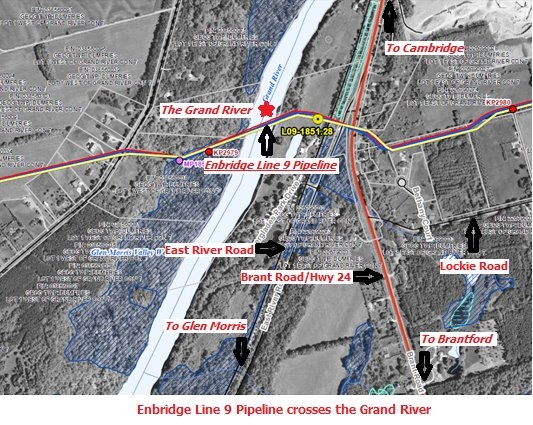

The pipeline, known as Line 9, has been buried under the Grand River and North Dumfries Township since the mid-1970s. It’s a major artery for foreign crude headed west to refineries in Sarnia, long forgotten and hardly noticed by residents here.

But a proposed change to Line 9 is bringing new concerns about the safety of the 40-year-old pipeline. Environmentalists warn that a plan by Calgary-based Enbridge Pipelines to reverse the direction of flow and start pumping crude oil eastward from Alberta could expose our region to contamination.

They warn that if Enbridge begins pumping watered-down bitumen crude from Alberta’s oilsands, a more corrosive version of light crude oil, the decades-old pipeline could be pushed to the limit.

They point to a major spill in the Kalamazoo River in Michigan after an Enbridge pipeline carrying bitumen ruptured less than three years ago, spilling 3.3 million litres of oil. That pipeline was of similar vintage as Line 9 and likewise not built for this new, riskier kind of crude oil, activists argue.

But the pipeline company says those concerns are overblown and argues the pipeline is a key piece of infrastructure for Ontario’s economy. It’s learned a lot since the Kalamazoo spill in 2010 and has beefed up its safety procedures, said spokesperson Graham White.

Local environmentalists aren’t convinced. They claim the project is a significant spill risk from a company with a history of causing environmental disasters.

“They have a pretty bad reputation, and that’s pretty scary for the people who are along the route of this pipeline,” said Paisley Cozzarin, a University of Waterloo student who founded Stop the Tar Sands KW, an offshoot of the Waterloo Public Interest Research Group.

Line 9 skirts through the countryside south of Ayr, along Wrigley Road, and crosses under multiple highways and waterways, including the Nith and Grand rivers. Small orange signs mark its burial underground, including a 10-metre wide pathway off Highway 24, just south of Cambridge.

It’s difficult to know for sure what shape the old pipeline buried under the Grand River is in, making the project too great an environmental risk, Cozzarin said.

Enbridge’s plan for the section of Line 9 that runs through Waterloo Region has already been approved by the National Energy Board. Opponents are now focusing their efforts on stopping the second phase of the project, which covers the pipeline from a pumping station east of Cambridge to Montreal.

In Quebec, the Parti Québécois government wants to conduct its own review of the pipeline. Alexandre Cloutier, the minister for Canadian intergovernmental affairs, says Quebec wants to make sure the pipeline follows its laws and regulations.

The push to send Alberta oil east through Ontario and Quebec comes at time when energy companies are encountering fierce resistance to new pipelines on the other side of the country, particularly in B.C.

TransCanada, another pipeline company that plans to convert some of its natural gas pipelines into oil lines to move crude eastward, told investors this week that it doesn’t expect much resistance to its plans in Eastern Canada.

Enbridge has said there are no plans to change the type of oil being pumped through Line 9. Activists’ claims that it will eventually carry more toxic, watered-down bitumen are unfounded, White said.

Line 9 will carry what it always has — tested, processed crude that is “clean and safe,” not raw heavy bitumen with toxic additives, he said.

“People who are making claims about heavier crude. … They’re capitalizing on a fundamental misunderstanding of what crude oil in transmission is,” said White. “The primary product to be shipped on this line is light crude, which is what they’re currently shipping.”

Adam Scott, climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence, says the company isn’t being up front about its plans for Line 9. He said getting permission to switch from light crude to bitumen is a matter of a small application to the National Energy Board after the project goes ahead.

“To avoid having to discuss this during the approval stage, they’ve stuck to their story that they’re just going to stick with light oil, for now,” he said.

Once the project is completed, the pipeline company wants to increase the volume flowing through Line 9 from the current 240,000 barrels to 300,000 barrels per day, Scott said.

Environmental Defence says a switch to bitumen would put water and farmland along Line 9’s route at greater risk of oil spills, because it’s harder and more costly to clean up. The environmentalist group argues the pipeline crosses major rivers that feed into Lake Ontario, “putting the drinking water for millions of people at risk.”

Enbridge, meanwhile, says it will beef up monitoring of Line 9 with regular inspections and do repairs where necessary.

That’s one of the lessons learned from the Kalamazoo River spill, which White called a “very significant event” that caused the company to improve its leak detection and control centre operations.

“We have learned as much as we can from that incident, and we’ve become a much safer and a much better company as a result,” White said.

There are economic reason for Ontarians to support the reversal of Line 9, he said. That includes work for construction crews doing inspection digs and giving Canadian refineries access to domestic crude, White said.

But people like Scott continue to question how much the company has really changed since the Kalamazoo River spill.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board was highly critical of Enbridge’s response to that leak. It found the company knew about roughly 15,000 defects in that pipeline for five years before the spill, but excavated to inspect just 900 of them.

When the pipeline ruptured, Enbridge’s control room staff in Alberta mistook alarms of a pipe break for a drop in pressure, and pumped extra oil through the pipeline instead of shutting it down. Seventeen hours passed before they realized they had a massive spill on their hands.

Activists hope these kind of stories can get the public and politicians on board to stop the Line 9 project.

“I think if there’s enough community resistance to these pipelines, it’s sending a message to the government that Canadians don’t want to deal with these risks,” Cozzarin said.

Louisette Lanteigne, another local activist, has organized a protest in Waterloo’s town square on Nov. 19 to draw attention to the Line 9 project.

- Log in to post comments